“Briefly put, the purpose of this whole work [the Divine Comedy] as well as its parts is to remove those living in this present state of life from misery and to lead them all the way to happiness. The kind of philosophy under which we proceed here both in whole and in part is the business of morals or ethics, since both the part and the whole are composed for practice rather than theory. But if in some place or passage things are lengthened out in the manner of theory, this is not for the purpose of theory, but of practice; for, as the Philosopher says in the second book of Metaphysics: “practical men theorize now and again.” – Dante

John Scotus Erigena was condemned posthumously by the Church, much like another John, John Philoponus. Both of these thinkers gravitated towards Greek philosophy, particularly Plato, though Philoponus was more eclectic and Erigena more overtly Platonic. In the sixth century, Justinian appointed John Philoponus to resolve the schisms in the Church. His work was shoved aside after it was completed:

I believe that Philoponus understood the infinity of the void as filled with a structure the extension of which was not the same as matter or energy in its particular place. It may be understood in theory as that dimension of the cosmos in which the universal and the singular are composes of one another without logical contradiction. It was in this sense a servant of the Lord God, the Creator of a world in which He was free to enter into as a man. Do not concepts like these help us to understand the dynamic definition he sought for when he wrote his argument for the divine and human person of Jesus Christ.

This exposition is similar to the defense of the distinction between Meon and Pleroma attempted by Gornahoor here.

God uses the Void (possibility?) to rule what is actualized. It is important to understand the invisible structure of Reality, because many experimenters or unwitting visitants (everyone, after death) get lost because of lack of renunciation & knowledge. In Christ the Eternal Tao Hieromonk Damascene notes that the existence of non-being (Meon) is real, and has been mistaken by many Western drug practitioners and others to be identical with God Himself, leading to unfortunate results. What seem to be trifles (such as the debate between universalism and nominalism via Occam) often are hinges upon which enormous cultural and metaphysical changes are leveraged. Philoponnus offered not only a truly “Greek” way of understanding the homo ouisos of the Creed so as to reconcile the Oriental Churches with the Orthodox, but also a metaphysic of reality which was in keeping with Plato.

The influence of Erigena was also enormous, even after the condemnations by the keepers of pristine rectitude – here is Nicholas of Cusa:

I say “creates” inasmuch as [this spirit] makes the conceptual likenesses of things from no other thing—even as the Spirit which is God makes the quiddities of things not from another, but from itself, i.e., from Not-other. And so, just as [the Divine Spirit] is not other than any creatable thing, so neither is the mind other than anything understandable by it.

What is interesting about Erigena is that he (also) shares the conception of something beyond Nature out of which Nature “stands”, and from which Nature can be ruled. This is the basic super-naturalism which offers the possibility for metaphysics. The root of this transference between Plato and “the Christians” can be posited to lie in Pseudo-Dionysius, arguably either the lone philosopher convert whom St. Paul made at Mars Hills in Athens, or a student of Origen’s at Alexandria.

As we often see in history, the origins of revelation often lie in the East, but their manifestation tends to appear in the West : “Westward the star of Empire makes its way”. Thus, Erigena’s philosophy represents an entirely faithful, yet more articulated and emphasized (and also simultaneously “pared down”) version of esotericism. Thus in the Periphyseon, Nature has four phases:

1. That which creates and is not created (God’s essence)

2. That which is created and creates (the world of Forms, or God’s Ideas, as well as Spirit)

3. That which is created and does not create (physical reality)

4. That which neither is created nor creates (the Void?)

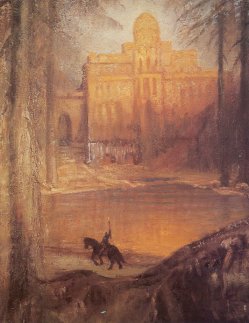

It is easy to see how the Church was made uncomfortable by this, and easy to predict the response. Until Hegel (who also veiled his esoteric side), Erigena’s influence (as we have seen in Cusa, but in others like St. Victor), remains underground, and instead the Church gravitates towards Pseudo-Dionysius in the architectural movement of the Gothic, which arguably included elements of the Templic Order. In other words, the Church has been continuously challenged, repelled, and shaken by the mysticism which it has tried to “contain” within it, but which would have ceased to be real esotericism had it acquiesced in this containment entirely.

It might behoove theologians to return to Philoponus and the Alexandrians, before the split which rendered esotericism an entirely encrypted or underground “manifestation” which dared not be “originating” in an open manner, but which had to be either sublimated into something like the Grail Mythos or “ab-original” in a purely philosophical or hidden manner.

By terrible and beautiful contrast, Dante the poet could still embody both orthodoxy and esotericism in his greatest work, and this high burning unification was brought about partly due to his emphasis on practice. But then, Dante was a champion of the Guelph monarchy, a bearer of gold, a singer of Apollo, an angel in the sun. Erigena and Philoponus might have understood the multi-leveled and complex layers of reality which could invoke such powers, because their metaphysics complemented their religion. One might even say that Neo-Platonism is Providentially intended to internally perfect the metaphysic inherent in the Faith.

(Dr Curran quoted Dante’s “Epistle to Cangrande della Scala”

Leave a Reply