whatever is is, and what is not cannot be ~ Parmenides

The Temptation of Parmenides

There is something disturbing to think that Fortuna has a place in our lives. There is a seeking after explanations, to explain what appears to be random. Parmenides believed so. For him, the world of phenomena, change, and motion is simply the manifestation of a changeless, eternal reality.

Superdeterminism is the analog in quantum physics for the metaphysics of Parmenides. Even Einstein was tempted by Parmenides since he believed that there had to be as yet undiscovered laws to explain the apparent randomness of quantum measurements. He famously rejected the idea of “spooky action at a distance”, which the notion of quantum entanglement implies.

Although physical laws can be deterministic within limits, quantum entanglement requires global determinism to make sense of it. That is why it is called superdeterminism. Sabine Hossenfelder is now the public face of superdeterminism. Let’s use a non-quantum metaphor to explain what she is getting at.

The Coin Flip

The sequence of heads or tails in a series of coin flips seems to be completely random. Randomness can be detected like this:

- The result of any coin flip does not depend on the result of the previous coin flips. A fortiori, it does not depend on a series of coin flips. The Gambler’s Fallacy, for example, is the belief that if a series of several Heads show up consecutively, then Tails becomes more likely.

- There are statistical tests that show the probability of randomness.

In the first experiment, the assistant tosses a coin 50 times and the physicist records the results. In a series of 100 experiments, the results are random and no pattern emerges. The results are used to train a neural network, but still no pattern emerges.

In the second experiment, an engineer monitors the coin tosses. At each toss, she measures the height of coin, the force imparted to it, and its angular momentum. Those are the hidden variables. With that information, she calls out the outcome of the toss. The physicist records the actual result and the predicted result. At the end of the experiment, the physicist notes that the predicted and actual outcomes match. Nevertheless, the results still appear random.

The physicist concludes that the hidden variables themselves are random; that would explain the experimental observations. The variability has been transferred to the coin tosser.

So the team plans to locate the hidden variables that control the tosser’s movements. But as far back as they go, even to the big bang, the experimental outcome still appears random. So even if the hidden variables are all known, for all practical purposes, the results always appear to be random.

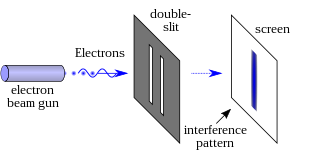

The Double Slit Experiment

Sabine uses the double slit experiment to illustrate superdeterminism. In that experiment, a beam of photons is sent through two slits, resulting in an interference pattern on a screen on the other side. That pattern is statistically random.

In the experiment, each photon will pass through the slit in which it expects to be measured. And unlike the engineer in the coin flip experiment, the hidden variable is not known until the photon is “measured”. As she points out,

The particle’s path depends on what measurement take place. Because the particles must have known already when they got on the way whether to pick one of the two slits or go through both.

So instead of spooky action at a distance, there is spooky action in the future.

Now that superdetrminism allegedly explains how photons choose their paths, the interference pattern on the screen remains seemingly random. Hence, the hidden variables must be randomly distributed. So the next level of hidden variables is also randomly distributed, all the way back to the big bang.

We agree that there is a hidden process that determines the motion of the photons, but it is not a physical process.

References

Superdeterminism and the dilemmas-around-free-will

Classical argument against free will

[youtube “https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ytyjgIyegDI”]

“This earthly part of the world is maintained by knowledge and practice of the arts and sciences, without which God has willed that it would not be brought to perfection. For what pleases God necessity obeys, as effect follows will; and it is not credible that what has pleased God will become displeasing to Him, since He knew long before, not only what would come to pass, but that it would please Him.”